I needed a quick, simple, one-player game that would give him an immediate reward for answering a solving a word problem correctly. It had to be fairly quick to play, because I planned to use it as part of our tutoring session. I also needed to have the answers available from a neutral source (so it wouldn't be me telling him if he was wrong), and there needed to be some kind of variability in the score-- partly skill, partly chance, to add interest. If he got the same score every time that would be kind of pointless.

|

| Left to right: Orange-covered answer key with two game cards on top, word problem side up; white game board with cards and game pieces; bottom: extra cards and game pieces. |

This particular game is done with a Pokémon theme, but can be translated into just about anything the student is interested in. The basic idea is that the student must answer a question correctly to move a game piece from one circle to the other. In this case, the game pieces are Pokémon, and the player rescues them as he moves each piece from the bad guys' side to the good guys' side. Another child might respond better to a game that features puppies being moved from the animal shelter to a home, cookies moving from the cookie jar to a plate, or princesses moving from the dragon's lair to a castle. The possibilities are endless. My student likes Pokémon, so that's what I used.

My game pieces were made from a dozen milk carton caps I had saved, but anything will work-- coins, poker chips, rocks, plastic figurines, Sculpey clay creations. The caps worked well for me because they were the perfect size to glue on small round Pokémon printables that I found online. (I glued a Poké Ball picture to the top of each cap, and then a different Pokémon character inside each one.)

The game board is just a Pages (Mac word processor) creation that has the two circles, the rules, and some graphics inserted from online images. Once I had it designed and printed out, I put it into a plastic page protector. Not only does this keep the board clean, but it also allows the student to write his scores on the page using a dry erase marker.

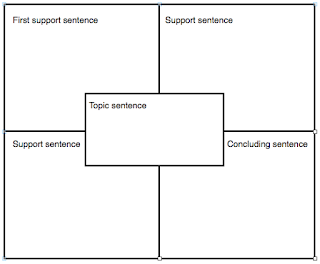

To make the game cards, I made a template using another word processing feature: the table. I inserted a table onto a new page and set it to have four columns and two rows, adjusting the height and width of the cells to approximate a card size. Then all I had to do was find an appropriate image to go on the back of each card. I inserted the image into every other cell, and then each of in the remaining spaces, I typed one of the student's word problems (from his textbook), replacing names and details with Pokémon characters and appropriate scenarios.

|

| This game board has a Pokémon theme, but it could be anything. |

I made 16 cards, using a total of 4 pages. After printing them out, I cut the cards out so that each blue Pokémon back could be folded over and have a word problem on the front. A bit of glue holds the two sides together, and viola! A stack of game cards.

|

| The game card template after the back image is inserted, before the word problem is added. |

To create an answer key, I used another table insert-- but this time, the table included the question number, solution process and final answer. Each card was labeled with a letter+number to correspond with its answer on the chart. To keep the student from seeing all the answers as he's checking for one, I made a cover sleeve for the answer key with a narrow window that shows only one answer at a time. To allow the answer key to slide up and down in the sleeve, I added a paper pull strip at the top of the key.

|

| This is the answer key chart. More problems and answers can be added later just by adding more rows to the table. |

- The student places 5 random game pieces (Poké Balls) in the bad guys' (Team Rocket’s) circle.

- The student places 5 random cards face down in the "cards" rectangle.

- The student draws a game card, reads the card and answers the question. If writing out the problem helps, that is allowed.

- The student check his answer with the Solution Chart.

- If he answered correctly, he chooses one game piece (Poké Ball) to move to the good guys' circle (Safety Zone).

- When all the cards are gone, the student tallies his points: in this case, 5 points for each regular Pokémon, 10 for Pikachu.

I specifically have the student choose only five game pieces and five cards per game, because solving five word problems are about the limit of "fun" as far as math goes-- even when Pokémon are at stake. Any more than that and I think the student would lose the thrill of the game.

If the game is made using a different theme, there needs to be a way to vary the points. This game is set up so that the student chooses look-alike Poké Balls without knowing what Pokémon are inside. Here are some other ideas:

- Hide colored beads under the caps, shell-game style, and have different point values depending on the colors of the beads. (In this case you might have to start with all the game pieces on the board and slide off the ones not selected before play begins, so that the player does not know which ones are under his chosen pieces.)

- Use a dry-erase marker to number the bottom of each game piece before the player chooses his pieces. This way, the point value for any piece can change with every game session.

It's hard to stay motivated to do your best when school days seem to bring nothing but more and more work. This particular game brought joy to my student today, and that made me happy, too!