Many students have trouble with writing paragraphs, let alone essays. For some, the difficulty lies in getting the ideas out of their heads and onto paper. There are too many things to think about all at once-- the ideas themselves, the words, the spelling, even the act of physically writing the letters can be an obstacle for some children. For others, the ideas are easy enough, but they tend to come out in a rambling, completely disorganized manner. Happily, both of these problems can be addressed.

For the first problem, that of expressing the ideas on paper, I have been most impressed by the techniques of Andrew Pudewa's Institute for Excellence in Writing (IEW). (And no, I have no stock in his company nor am I being compensated for mentioning it.) While some people whose children are blessed with a natural talent for writing might cringe at his methods and call them "formulaic" (or worse), there is a definite population of students who benefit from his carefully incremental approach. The child who sits and cries over his writing assignments, for whom writing three sentences is like pulling teeth, will find IEW a relief.

The problem for these students is that converting their thoughts into words feels like a Herculean task. They can speak just fine, but somehow slowing their brain down enough to translate thoughts into written sentences is near impossible. So IEW takes a step back, and has students first translate someone else's ideas into sentences. They begin by reading short paragraphs and making a "key word outline," choosing two or three of the most important words from each sentence. The student then creates a new sentence for each set of words. (In effect, he is also learning to take notes without plagiarizing!) Here is an example, using the paragraph I wrote above as the original text:

Of course, the vocabulary in my original paragraph is not suited to a young reader or writer, but I hope you get the idea. Once the student has had practice with writing key word outlines and turning them into new paragraphs, he is introduced to the idea of writing key word outlines from the information in his own head. The student is then not overwhelmed, because he is able to get all of his ideas down, a few words at a time, before going back to construct complete sentences. When this process has become easy, the student begins to add complexity to his sentences by adding "dress-ups," such as introductory phrases, precise nouns, verbs, adverbs and adjectives, and various sentence constructions.

Some students have no trouble at all writing complete sentences, but need help organizing them into a coherent paragraph. They may be used to typing away on a computer, and think creating an outline is an unnecessary step. The result is a disorganized mess. The concept of paragraph structure doesn't register at all.

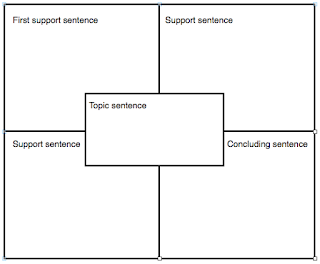

There are many graphic organizers that are helpful for this. One very effective system was developed by J.S. and E.J. Gould, called the Four-Square Writing method. (No compensation here, either.) In this method, the paragraph is visualized as a block divided into sections, so that the topic sentence, supporting ideas and conclusion are presented as a unit. This not only helps the students to remember to include each element, but also helps them understand that all of the pieces work together.

Here is one example of a Four Square graphic organizer. Note that the topic sentence bar touches each of the other sections, and all of the sections together form a single square.

While the graphic organizer may be helpful on its own, the Goulds have developed a program of sequential lessons for various ages of students that help the students understand what makes a good topic sentence, how to write good supporting sentences, and how to conclude a paragraph without simply restating the topic sentence.

Here's an example of the organizer filled out with supporting details, topic and concluding sentences.

For the record, there is "mind-mapping" software such as FreeMind or SimpleMind that will guide a student through placing sentences in a graphic organizer, and then turn these words into an outline; these may be helpful for certain students. In my experience, however, I have not seen any such programs that get across the idea of paragraph cohesion to the same degree as the simple Four Square box. Once the student understands paragraph structure, the mind-mapping may be great, but until then it's just another tool to make his ramblings more complex.

Whether your student needs help getting the words on paper or just getting the words organized, the best approach is to start where he is and proceed at a comfortable pace. Slow and steady wins the race!

A blog devoted to making math concepts, reading, spelling and writing skills accessible to K-8 students through hands-on activities.

Showing posts with label writing. Show all posts

Showing posts with label writing. Show all posts

Tuesday, October 13, 2015

Wednesday, August 26, 2015

Four Easy Reading/Writing Tips

Here are some common reading and writing problems and ways to work on them. The first two have to do with individual words, the last two with longer passages:

1) When a student reads aloud, he misreads words, substituting similar words, such as "medical" for "mechanical." Note how the words begin and end the same way-- the brain is tempted to fill in the middle with a word it already knows, especially if the actual word on the page is unfamiliar. The brain must be trained to look at the middle part, too.

The best way to do this is to have the student divide the word into syllables. This can be done on paper, underlining or drawing lines on the printed word: me/chan/i/cal. (Note: this is a good time to remind the student that ch can represent three sounds: Chocolate, Christmas, and Charlotte.) Using 3-D manipulative letters or tiles is especially helpful, because they move freely and the student can put the word together and apart easily. Even letters written on small squares of paper can be used. Alternatively, the word can be written whole and cut up into syllables. The important thing is that the student becomes so adept at breaking up the word physically that he begins to see the words that way, and breaks them up mentally without thinking.

2) When a student has to spell a long or difficult word, he may put in the wrong letters, or can't remember which letters are correct. Have him look at the word syllable by syllable. Practice with 3-D letters as explained above.

The preceding tips were for single-word errors; now, let's look at a couple of common problems students have when reading paragraphs or articles:

3) When a student is called upon to determine the main idea, or central idea, of a passage he is reading, he chooses a sub-point from the passage instead. The task is harder than it sounds, especially while the brain is still developing abstract thought. Students must not only read and comprehend the information, but they must mentally sort supporting details from over-riding themes.

To practice this, have students start with easy part-whole exercises, such as "Parts of a house" "roof" "wall" "window" "door" "foundation." If you have two identical pictures of a house, and cut one up, the student gets the idea quickly. Put the whole house picture at the top of the desk, and line the parts up below it. The idea is for the student to see that the "main idea" includes all of the supporting details. And each supporting detail is a part of the main idea.

Similarly, you could use "parts of an ice cream sundae" "ice cream" "chocolate sauce" "whipped cream" "nuts" "cherry," or "animals on the farm" "cow" "horse" "pig" "goat" "chicken." Then move on to words instead of pictures.

Finally, give your student a set of several entire sentences instead of words-- cut them into sentence strips and have your child find the one which works best as the main idea. Can you pick the main idea from this set?

If your student has trouble sorting the sentences, have her underline 3-4 key words from each sentence. This will help her focus on what each sentence is about. In this way, she can see that of the sentences above, most are about individual desert animals. Only one has the general "many animals" as its topic; this is the main idea that all the other more specific sentences fall into. Some students will need a lot of practice with this skill.

If the student is supposed to come up with the main idea on his own, or choose between a few given possibilities, have him write facts from the passage on sticky notes. Write possible "main idea" choices on a white board. See which main idea choice can have all facts fit underneath it.

Writing a cohesive paragraph requires the same understanding of main idea and supporting details. The only difference is that the student has to decide what details to include in order to support his main idea. So when your child can easily distinguish between main idea and supporting details, try giving him a set of main idea and supporting details with an added red herring-- an off-topic detail for him to identify and discard. For example, in the list above, an off-topic detail would be, "Dolphins prefer the warm waters of the Pacific Ocean." When he can find one, try giving him a set with more than one discardable detail. This will help him when he looks at his own writing. At that point, writing his thoughts on a graphic organizer such as one of these might help him develop his paragraph(s).

4) A student comprehends what he reads, but can't skim for information that he needs quickly. He doesn't change his reading speed whether he is reading for pleasure or for information. While most students have been taught to read through the questions on an assignment so they'll know what to look for in the text, they often don't realize that reading every word of the text is not always the best means of then finding that information. Sometimes they just need to know a certain fact. So they need to be able to focus their search logically. For example, if a student is looking through a passage for the answer to "How far is the earth from the sun?" ask her what are the most important words in the question. How far, earth, sun. What words might be in the answer? Earth, sun, and some number.

When the student understands that she is looking for a number and the words "earth" and "sun," she must then be able to skim efficiently through the passage, ignoring everything that isn't a number or those two words. Just as importantly, having found the words and/or a number, the student should be able to read the sentence they appear in to verify that it does indeed answer the question.

Skimming is an eye+brain discrimination skill, and takes practice. It is one of the skills honed in word searches and those 'hidden pictures' games we enjoyed as children. But there are ways to build proficiency; when the student knows she is looking for numbers, for example, she can try to underline all the numbers. That will help the brain focus. Also, when looking for a particular word, she can get a picture in her mind of what that word will look like. A good way to practice is to pick a page of a book at random and ask the child to find a specific word. Make it a word that is at least half-way down the page at first; then try other words that may be nearer the top or bottom of the page. The student should try to find it as fast as possible.

These four tips are not overnight game-changers, but with practice, can make a difference in how well your child reads and performs in school.

1) When a student reads aloud, he misreads words, substituting similar words, such as "medical" for "mechanical." Note how the words begin and end the same way-- the brain is tempted to fill in the middle with a word it already knows, especially if the actual word on the page is unfamiliar. The brain must be trained to look at the middle part, too.

The best way to do this is to have the student divide the word into syllables. This can be done on paper, underlining or drawing lines on the printed word: me/chan/i/cal. (Note: this is a good time to remind the student that ch can represent three sounds: Chocolate, Christmas, and Charlotte.) Using 3-D manipulative letters or tiles is especially helpful, because they move freely and the student can put the word together and apart easily. Even letters written on small squares of paper can be used. Alternatively, the word can be written whole and cut up into syllables. The important thing is that the student becomes so adept at breaking up the word physically that he begins to see the words that way, and breaks them up mentally without thinking.

2) When a student has to spell a long or difficult word, he may put in the wrong letters, or can't remember which letters are correct. Have him look at the word syllable by syllable. Practice with 3-D letters as explained above.

Careful correct pronunciation, or over-pronunciation, can be helpful in distinguishing which vowels to use. For example, "ridiculous" is easier to spell if you pronounce it as rid-ih-cu-lus instead of ree- dic-you-luss." “Difficult” is easier to spell if you say diff-ih-cult and not diff-uh-cult.

If a word is particularly tricky, mentally mispronouncing the word (phonetically) on purpose can help her remember how it is spelled. For instance, say "deter + MINE" instead of "deter + men." "Rendezvous" is easy to remember if you say it in your head as "rehn" "dez" "voos" instead of "ron" "day" "voo." "Perseverance" is easier to spell "per + sev + er + ance " but be careful not to say “enss” at the end.

The preceding tips were for single-word errors; now, let's look at a couple of common problems students have when reading paragraphs or articles:

3) When a student is called upon to determine the main idea, or central idea, of a passage he is reading, he chooses a sub-point from the passage instead. The task is harder than it sounds, especially while the brain is still developing abstract thought. Students must not only read and comprehend the information, but they must mentally sort supporting details from over-riding themes.

To practice this, have students start with easy part-whole exercises, such as "Parts of a house" "roof" "wall" "window" "door" "foundation." If you have two identical pictures of a house, and cut one up, the student gets the idea quickly. Put the whole house picture at the top of the desk, and line the parts up below it. The idea is for the student to see that the "main idea" includes all of the supporting details. And each supporting detail is a part of the main idea.

Finally, give your student a set of several entire sentences instead of words-- cut them into sentence strips and have your child find the one which works best as the main idea. Can you pick the main idea from this set?

- Tortoises and lizards, spiders and scorpions are desert inhabitants.

- Many animals make their home in the desert.

- The javelina, or peccary, enjoys the cactus fruit in late summer.

- Jack rabbits hide among the prickly pear.

- Snakes of many kinds roam the desert floor and sun themselves on rocks.

- Coyotes roam the desert in search of prey.

If your student has trouble sorting the sentences, have her underline 3-4 key words from each sentence. This will help her focus on what each sentence is about. In this way, she can see that of the sentences above, most are about individual desert animals. Only one has the general "many animals" as its topic; this is the main idea that all the other more specific sentences fall into. Some students will need a lot of practice with this skill.

If the student is supposed to come up with the main idea on his own, or choose between a few given possibilities, have him write facts from the passage on sticky notes. Write possible "main idea" choices on a white board. See which main idea choice can have all facts fit underneath it.

Writing a cohesive paragraph requires the same understanding of main idea and supporting details. The only difference is that the student has to decide what details to include in order to support his main idea. So when your child can easily distinguish between main idea and supporting details, try giving him a set of main idea and supporting details with an added red herring-- an off-topic detail for him to identify and discard. For example, in the list above, an off-topic detail would be, "Dolphins prefer the warm waters of the Pacific Ocean." When he can find one, try giving him a set with more than one discardable detail. This will help him when he looks at his own writing. At that point, writing his thoughts on a graphic organizer such as one of these might help him develop his paragraph(s).

4) A student comprehends what he reads, but can't skim for information that he needs quickly. He doesn't change his reading speed whether he is reading for pleasure or for information. While most students have been taught to read through the questions on an assignment so they'll know what to look for in the text, they often don't realize that reading every word of the text is not always the best means of then finding that information. Sometimes they just need to know a certain fact. So they need to be able to focus their search logically. For example, if a student is looking through a passage for the answer to "How far is the earth from the sun?" ask her what are the most important words in the question. How far, earth, sun. What words might be in the answer? Earth, sun, and some number.

When the student understands that she is looking for a number and the words "earth" and "sun," she must then be able to skim efficiently through the passage, ignoring everything that isn't a number or those two words. Just as importantly, having found the words and/or a number, the student should be able to read the sentence they appear in to verify that it does indeed answer the question.

Skimming is an eye+brain discrimination skill, and takes practice. It is one of the skills honed in word searches and those 'hidden pictures' games we enjoyed as children. But there are ways to build proficiency; when the student knows she is looking for numbers, for example, she can try to underline all the numbers. That will help the brain focus. Also, when looking for a particular word, she can get a picture in her mind of what that word will look like. A good way to practice is to pick a page of a book at random and ask the child to find a specific word. Make it a word that is at least half-way down the page at first; then try other words that may be nearer the top or bottom of the page. The student should try to find it as fast as possible.

These four tips are not overnight game-changers, but with practice, can make a difference in how well your child reads and performs in school.

Thursday, July 23, 2015

Whole Brain Writing

I love the Whole Brain Teaching philosophy. It uses physical movement, oral repetition and response, and visual images to teach. It is high energy, fun, and highly effective. I used WBT's Superspeed Math drills and a few other techniques the year before I quit teaching.

Whole Brain Writing is a free download at Chris Biffle's Whole Brain Teaching website. To get it, create an account on the website (free!) and download the material from the "Goodies" menu. It is presented as a slideshow, but is very easy to follow. In fact, you could easily use the slideshow as the basis for your own classroom (or your own child's) writing curriculum.

The program starts out giving definitions and accompanying hand gestures to teach parts of speech. There are also hand gestures to teach sentence rules (capitalization and end punctuation), topic sentence, paragraph, and essay. Students practice 'oral writing" with these gestures-- answering questions in complete, capitalized and punctuated sentences-- and are challenged to support their answers with gesture-emphasized "because" statements. The function of the gestures is not unlike Signed English-- which is a bridge between ASL, with its unique vocabulary, grammar and syntax, and the English that deaf students learn to read. WBT's "oral writing" is a similar bridge between students' spoken language and the written conventions.

The program then provides several activities with graphic organizers for expanding students' thinking and writing from brainstorm charts to complete essays. These include WBT Brainstorming, the Genius Ladder, and Triple Golders.

WBT Brainstorming takes students through creating "who, what, when, where, why, how" questions about their topic and then answering them in a way that can create complete, organized essays.

The Genius Ladder is presented as a game that helps students develop a simple sentence into a more complex, descriptive one, adding details and "extenders," and organize the sentences into paragraphs. It reminds me of the step-by-step approach of Andrew Pudewa's Institute for Excellence in Writing (IEW), and I suspect it would work for the same type of student. Pudewa starts his students out writing "key word outline" notes from published material, and they end up writing detailed original sentences with specific "dress-ups" in organized paragraphs and essays. In WBT's Genius Ladder, students move from the "blah sentence" to the "genius paragraph."

With Triple Golders, students begin with simple, scaffolded sentence frames and learn to create detailed sentences that they can expand into tightly organized paragraphs and essays.

And about that grammar... Superspeed Writing is an activity that helps students practice constructing sentences using various parts of speech, beginning with "I see a (noun)," and ultimately completing "Article adjective noun, appositive, verb adverb prepositional phrase conjunction rest of sentence."

As if that wasn't enough, Biffle provides a fun, low-stress method for getting students to notice their own errors and not meltdown when their errors are pointed out to them. For red-green proofreading, students mark each other's papers, once with a red marker to identify an error ("less perfect skill"), and once with a green marker ("more perfect skill.")

And as with all WBT programs, it is the individual student's progress that is celebrated, not just the top banana. So everybody stays motivated.

Here's another activity, called SuperSpeed Reading, that is a fun way to drill sight words in a large classroom. It is similar to WBT's Superspeed Math, which I have used with success to drill math facts.

If you are at all interested in adding these hands-on, whole brain activities to your writing classroom, check out the Whole Brain Teaching website!

Whole Brain Writing is a free download at Chris Biffle's Whole Brain Teaching website. To get it, create an account on the website (free!) and download the material from the "Goodies" menu. It is presented as a slideshow, but is very easy to follow. In fact, you could easily use the slideshow as the basis for your own classroom (or your own child's) writing curriculum.

The program starts out giving definitions and accompanying hand gestures to teach parts of speech. There are also hand gestures to teach sentence rules (capitalization and end punctuation), topic sentence, paragraph, and essay. Students practice 'oral writing" with these gestures-- answering questions in complete, capitalized and punctuated sentences-- and are challenged to support their answers with gesture-emphasized "because" statements. The function of the gestures is not unlike Signed English-- which is a bridge between ASL, with its unique vocabulary, grammar and syntax, and the English that deaf students learn to read. WBT's "oral writing" is a similar bridge between students' spoken language and the written conventions.

The program then provides several activities with graphic organizers for expanding students' thinking and writing from brainstorm charts to complete essays. These include WBT Brainstorming, the Genius Ladder, and Triple Golders.

WBT Brainstorming takes students through creating "who, what, when, where, why, how" questions about their topic and then answering them in a way that can create complete, organized essays.

The Genius Ladder is presented as a game that helps students develop a simple sentence into a more complex, descriptive one, adding details and "extenders," and organize the sentences into paragraphs. It reminds me of the step-by-step approach of Andrew Pudewa's Institute for Excellence in Writing (IEW), and I suspect it would work for the same type of student. Pudewa starts his students out writing "key word outline" notes from published material, and they end up writing detailed original sentences with specific "dress-ups" in organized paragraphs and essays. In WBT's Genius Ladder, students move from the "blah sentence" to the "genius paragraph."

With Triple Golders, students begin with simple, scaffolded sentence frames and learn to create detailed sentences that they can expand into tightly organized paragraphs and essays.

And about that grammar... Superspeed Writing is an activity that helps students practice constructing sentences using various parts of speech, beginning with "I see a (noun)," and ultimately completing "Article adjective noun, appositive, verb adverb prepositional phrase conjunction rest of sentence."

As if that wasn't enough, Biffle provides a fun, low-stress method for getting students to notice their own errors and not meltdown when their errors are pointed out to them. For red-green proofreading, students mark each other's papers, once with a red marker to identify an error ("less perfect skill"), and once with a green marker ("more perfect skill.")

And as with all WBT programs, it is the individual student's progress that is celebrated, not just the top banana. So everybody stays motivated.

Here's another activity, called SuperSpeed Reading, that is a fun way to drill sight words in a large classroom. It is similar to WBT's Superspeed Math, which I have used with success to drill math facts.

If you are at all interested in adding these hands-on, whole brain activities to your writing classroom, check out the Whole Brain Teaching website!

Wednesday, June 10, 2015

My favorite manipulatives for teaching spelling, reading and writing

What are golf balls doing in an article about teaching literacy, you ask? Well, I'll go into more detail in another blog, but the short version is they can help the student learn to identify the sequence of sounds in a word. Colored tiles, pieces of colored paper, beads, Legos, and many other things can serve the same purpose. This technique in various forms is found in Carmen McGuinness' Reading Reflex, Susan Barton's Barton Reading system and other literacy programs.

What are golf balls doing in an article about teaching literacy, you ask? Well, I'll go into more detail in another blog, but the short version is they can help the student learn to identify the sequence of sounds in a word. Colored tiles, pieces of colored paper, beads, Legos, and many other things can serve the same purpose. This technique in various forms is found in Carmen McGuinness' Reading Reflex, Susan Barton's Barton Reading system and other literacy programs.

The other items I have pictured here are more obvious-- the alphabet puzzle, Scrabble tiles, and letter stamps can be used to play with the sounds in a word to practice both reading and spelling.

The colored pencils are used to mark spelling patterns in words and divide them into syllables. When we were homeschooling, one of the best spelling programs we used was The Writing Road to Reading. An important component of this program was having the students mark the sounds represented in each word, and identify rules that applied to each. For example, each occurrence of silent e was numbered according to which of the five reasons for using a silent e was in force. It was a tedious process, but was very helpful for my children.

Recently I have seen a newer program, Spelling You See. This one looks like a keeper! It is put out by the Math-U-See people. This program also has the student marking spelling patterns, and includes workbooks to make things less tedious. There is a dictation component, as recommended by education gurus from Charlotte Mason to Susan Bauer, so the students are analyzing words in context. If I were homeschooling today, I would definitely give this one a try.

While "hands-on" is not the first thing one might think of when the subject of literacy comes up, there are actually many techniques and tools that can help a child build a foundation for reading and writing. In future blog posts, I will go into more specifics.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)